25 Mar 2020

A Tale of Two Pandemics: a plea on World TB Day, 24 March 2020

LIV-TB is a cross-campus collaboration between the Liverpool

School of Tropical Medicine and the University of Liverpool. In the following

post, Dr Tom Wingfield talks about the current TB Pandemic.

It is the worst

of times. We are facing a pandemic.

A quarter of the world’s population is estimated to be infected.

By the end of 2020, it is likely that 10 million people will have fallen ill,

three million will not have been tested and treated, and over 1 million, mostly

vulnerable people, will die.

This pandemic is not caused by the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2,

which leads to COVID-19.

It is caused by tuberculosis (TB).

Yesterday, on World TB Day 2020, and amid this

unprecedented outbreak, we at LIV-TB and others think

it is vital to compare and contrast the TB and COVID-19 pandemics - one old,

one new - to remind ourselves why it’s still time to end TB. We

have written a related comment that has been published here in Lancet

Respiratory Medicine.

So what is a pandemic? A pandemic is defined as

a disease that spreads over a whole country or the whole world. TB and COVID-19

both fit this definition, affecting people across all six continents. No

country is TB free and COVID-19 has now reached more than 180 of the nearly 200

countries on the planet.

There are striking similarities between the two pandemics.

Both are a huge cause of illness and death around the world. TB is the single

biggest infectious diseases killer, ending the lives of 1.2 million people in

2018. This is more than HIV and malaria combined. COVID-19 has infected nearly

250,000 people and caused nearly 10,000 deaths in the first quarter of

2020 alone.

Both cause symptoms

of fever, cough and shortness of breath. In countries with escalating

COVID-19 cases, this is likely to mean that people with TB presenting to

clinics and hospitals may go unrecognised or misdiagnosed. A similar pattern

emerged in West Africa when cases

of malaria were missed during the Ebola outbreak. Another similarity is

that those at higher risk of more severe TB and COVID-19 disease and outcomes

are older people

and those with chronic illnesses. And, as we are discovering for COVID-19,

both diseases lead to significant social impact including stigma, discrimination,

and isolation;

and economic impact related to country

productivity losses and catastrophic

costs to individuals and households.

There are also stark differences, the first being time. TB

has accompanied us for thousands of years even being found in Egyptian

mummies. SARS-CoV-2, on the other hand, is a new coronavirus that has

spread rapidly around the world since December 2019. TB, previously known

as consumption

or The White Plague, is used to being labelled a pandemic. This is the

first COVID-19 pandemic humankind has ever seen. Second, most children with

COVID-19 will

have only mild symptoms. The same cannot be said for TB, which in

2018 killed

one in five of the 1.1 million children who became ill with TB. Finally,

over 90% of TB cases and deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries. In

contrast, Europe has been called the second epicentre of

COVID-19 after China. Among other factors, this may explain why more

funding and person-power will be put into the COVID-19 response in a year than

TB has received in decades. However, modelling studies show us that vulnerable

countries in sub-Saharan Africa and the Americas will soon be dealing with

their own COVID-19 epidemics. We must all act together now to prevent

a catastrophe.

There remain many unknowns. How TB and COVID-19 may interact

is not understood. Put simply, TB rates could go up due to more people coughing

due to COVID-19 who also have TB or go down due to self-isolation and

quarantine. The risk factors for getting COVID-19 and having more severe

disease appear to overlap and be similar to those for TB. These include being older, a

smoker, male,

having other chronic

illnesses such as lung disease, and being poor. Undoubtedly, COVID-19, like

TB, will be associated with the medical

poverty trap, in which poorer people have a higher likelihood of infection,

disease, and adverse outcomes. Also, unemployed people, informal or zero-hour

contract workers, will experience further impoverishment, which increases

TB risk.

The best of times would be to live in a COVID-19 and TB-free

world. But this is a long way off and there is much to do. So, as we work

together to control COVID-19, let's not forget the ongoing TB pandemic; still

the biggest infectious diseases killer. We need to markedly increase funding to

strengthen healthcare systems to address TB and to support research for a

vaccine, better tests and medicines, equitable access to care, and socioeconomic

support for people affected by TB. We need to continue to inform, advocate

for, and empower local communities and to lobby

governments and policymakers, to ensure that TB, as well as COVID-19,

remain high on the global agenda. The lessons we have been taught by pandemics,

old and new, are to be proactive, long-sighted, to plan ahead, and to not

become complacent.

Let's look forward to the best of times.

Read the full

Lancet Respiratory Medicine article.

25 Sept 2019

An overview: HIV vaccine approaches at IGH

There are two major types of the human immunodeficiency virus or HIV, HIV-1 and HIV-2, and current treatment for HIV-1 is with life-long antiretroviral therapy. In this blog, IGH researchers Professor Bill Paxton and Dr Georgios Pollakis updates us on recent developments in HIV-1 vaccine approaches.

HIV-1 is the most common form of the HIV virus, and research

to produce a vaccine is still ongoing. There is still considerable debate as to

what is going to result in a successful HIV-1 vaccine, either preventative or

therapeutic, and which strategies should be best employed to do so. It is still

relatively unknown which combination of cellular or antibody immune responses

are going to provide the optimal immunity required. The group of Bill Paxton

and Georgios Pollakis are involved in two EU funded programmes analysing two

different approaches, one is a T cell approach (a type of cell that forms the

immune system) and the other is antibody (a protein produced by the immune

system to neutralise pathogens).

The ongoing H2020 funded European HIV-1 Vaccine Alliance

programme includes HIV-1 infected individuals boosted with a substance designed

to stimulate the immune system (an immunogen) aimed at heightening the response

of T-cells to HIV-1. Participants receiving successful antiretroviral therapy

will be vaccinated with a regime of a T-cell boosting immunogen after which they

will be taken off therapy (treatment interruption) and time to viral rebound and

to what extent measured. This will include a control arm to which time to viral

rebound can be compared. During the vaccination protocol cellular immune

responses will be measured by looking at HIV-1 viral loads. Furthermore, this

study incorporates an arm receiving immunogen/placebo along with a special

antibody (Vedolizumab) that has been linked with heightened immune response in

the body’s mucosal linings. This study will identify whether therapeutic vaccination

can provide benefit through increased elimination of HIV-1 infected cells and

control of virus spreading through the blood.

An EDCTP EU (bnAb-baby) funded proposal (started May 2019) is

a vaccine proof of concept study looking to address whether neutralising

antibodies have the potential to prevent HIV-1 infection in infants. A highly

potent human neutralising antibody (VRC-007LS) will be administered to HIV-1

negative infants being breastfed by HIV-1 positive mothers. It is known that

HIV-1 transmission can occur via this route even though mothers receive

antiretroviral therapy. Breakthrough cases will be identified where virus being

transmitted will be studied. These results will indicate whether high levels of

circulatory antibodies have the potential to block HIV-1 transmission via this

route of exposure and identify how potent they can be, whilst at the same time

providing an indication of potential viral escape. How to induce such antibody

responses would be the obvious aim stemming from these results.

For vaccines to be successful they will likely have to induce immune

responses that can clear HIV-1 ‘hiding’

in a resting or latent state in our own immune cells, or prevent the early

establishment of such cells in newly infected individuals. Therefore, better

understanding the cellular molecular environments that induce latency or

support active viral replication is relevant to not only therapy but also

vaccine success. Conversely, using therapeutic vaccines to activate T-cells may

well enhance the possibility of HIV-1 transmission as well as virus replication

in the case of therapeutic vaccines. Indeed, there are indications that the

failure of the STEP vaccine trial, where more infections were reported among

vaccine recipients than placebos, was due to cell activation and recruitment of

cells to sites of exposure and thereby increased transmission. We are therefore

actively involved in better understanding the molecular events that lead to

increased infection and replication and are currently studying such mechanisms

using cellular materials from the participants within our vaccine trials.

Certain types of parasite are known to change the immune

response of their host through dampening or skewing T cell activation, to avoid

the host immune system. Our most recent work (Mouser et.al. PLoS Pathogens e1007924,

5th Sep 2019) demonstrates that two different antigens (kappa-5 and

omega-1) from parasitic blood flukes can differentially effect HIV-1 interactions

with the immune system. Kappa-5 has been shown to bind dendritic cells (part of

the immune system) and can prevent viral capture and transfer, whilst omega-1

matures dendritic cells towards skewing T cells with a reduced capacity to

support HIV-1 replication. These results indicate that co-pathogen interactions

can alter HIV-1 transmission as well as subsequent viral replication. Vaccines

that induce a similar immune response would therefore be advantageous as they

would reduce the detrimental effects mentioned earlier, such as increased virus

replication and transmission.

9 Jul 2019

Meet the Researcher: Professor Alan Radford

Hannah Williams is a Year 10 Work experience

student spending a week learning about the research and communication activity

of IGH. Here, she interviews IGH’s Professor Alan Radford to find out about his

work and why it’s important.

Alan Radford is Professor of Veterinary Health Informatics at the

University Of Liverpool. His job entails teaching vet students about viruses of

relevance to animals and public health, and researching the use of big data to

improve the health of animals and their owners.

As part of his work he leads SAVSNET (Small Animal Veterinary

Surveillance Network), a project which uses electronic health data and which

monitors the many diseases or infecting organisms tested for at veterinary

diagnostic laboratories across the UK. The latter data can be analysed alongside

real-time data recorded at the end of consultations from participating

veterinary surgeons to monitor, for example, what antibiotics are being

prescribed and whether antibiotic resistance is present in bacteria causing

infections in animals. Moreover, SAVSNET helps to make information accessible

for all, which will increase awareness and knowledge of diseases in the small

animal population in the UK.

So how does research on big data helps us understand health in animals?

Animals are a big part of our lives, recent statistics show 49% of adults in

the UK own a pet. We also eat animals, as well as keeping them as companions,

therefore their welfare is very important to us.

How does this benefit society? Not only do we want our animals to be

happy and healthy but the health of animals can impact our health too. For

example, if your dog has an illness there is a chance it may be passed onto

you. To ensure this doesn’t happen, big data is a new way to better understand

diseases that could be passed to humans and reduce these diseases.

What impact will this research have? The data collected shows all types

of ill health in animals, therefore by looking at disease, SAVSNET can identify

new ways to reduce the risk of diseases. An example of their work is chocolate

poisoning in dogs. We all know that chocolate is poisonous to dogs, however do

you know what time of the year chocolate poisoning most often occurs? Through

using big data, they found Christmas was in fact the most common time of the

year for chocolate poisoning in dogs to occur. Using this information, owners

can be reminded to be careful where they leave chocolate lying around at

Christmas and it enables vets to be aware they may have more cases of chocolate

poisoning in dogs during the Christmas period.

What changes do you hope to see? SAVSNET will help to understand

individual diseases, how common they are in vet practice, which animals are

most likely to be affected, what are the best treatments and best ways to avoid

disease in the small animal population of the UK.

Currently, Professor Alan Radford is working on a variety of diseases,

as well as antibiotic use, tumours, rabbit dental disease and fleas

infestations. When asked what made him want to become a researcher he said he

never planned to; he wanted to be a vet, however after he got his veterinary

degree, he discovered he wanted to create new knowledge and understand animals

at a population level where he could have broad impact on improving animal

health.

Finally, some of his favourite things about his job include working with

people, being stretched to think of new ways of doing things, with every day

different and that he is starting to see the research he is doing have an

impact.

25 Jun 2019

Learning with the Experts - Liverpool Neuro ID Fellowship 2019

Learning with the Experts - Liverpool

Neuro ID Fellowship 2019

Sofia Valdoleiros is a Portuguese medical resident in Infectious Diseases and from

January until March 2019, caried out a clinical and academical internship in

Neurology, with a primary focus in Neurological Infection, with the Liverpool

Brain Infections Group (LBIG), under Professor Solomon, also with Dr. Benedict

Michael and Dr. Christine Burness.

The academical module took place at the Institute of Infection and

Global Health (IGH), where I was so well received and involved in the

activities by everyone. Along with the academical work I developed, I got to

participate in the Liverpool Brain Infections Group meetings, which included

the discussion of major research projects, such as Enceph-UK, and UK-ChiMES, major

programmes on adult and paediatric encephalitis. I even heard from Professor

Solomon himself on “How to write a winning grant”! I was given the opportunity

to attend international meetings of ground-breaking multicentre projects, such

as Brain Infections Global and ZikaPLAN, and what an honour it was to be able

to take part in these meetings and actually meet world leaders in Neurological

Infectious Diseases research!

Exciting activities seem to be always happening, such as these meetings

or Neuroscience Day or open

discussions about neuroscience research. I was sad my internship ended before

some other events took place, such as the Big

Infection Day or the Neurological

Infectious Diseases Course, but these sure were “replaced” by other

activities, such as the e-learning Neuro ID

Course or teaching sessions with Dr. Benedict Michael, who invested a lot

of time in discussing fascinating Neuro ID cases with me.

The clinical module took place at the Walton Centre and the Royal

Liverpool University Hospital. As a renowned neurosciences medical centre, at

the Walton Centre it is possible to attend experts’ subspecialty Neurology

Clinics, observe inpatients with neuro-infection and attend stimulating

meetings, from Grand Rounds to Lectures from Neurology experts and teaching

sessions, and MDT meetings such as Spinal Infection, Infection Control or

Neuroradiology. At the Royal, I accompanied Dr. Burness, a Neurology consultant

with a special interest in Neurological Infection, in observing referrals from

the ID wards, and attended the Neuro ID Clinic, an innovative approach bringing

together a Neurology consultant (specialized in Neurological Infection –

Professor Solomon, Dr. Michael and Dr. Burness) and an ID consultant (Dr.

Defres) in a multidisciplinary view of the patient. I was also given the

opportunity to attend the Encephalitis MDT monthly meeting at the National

Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London. I am so grateful for the

opportunity to learn from these Neuro ID experts’ experience and for their

valuable insights. It will certainly change my approach of the neuro infected

patient in Portugal.

Overall, the major point I highlight is the amount of opportunities (to

learn, to participate in) I was given in only 3 months. With so much and so

interesting and versatile things to do, these 3 months just completely flew by.

Thank you so much to everyone!

25 Apr 2019

Measles: should vaccinations be compulsory?

Following a measles outbreak in Rockland County in New York State, authorities there have declared a state of emergency, with unvaccinated children barred from public spaces, raising important questions about the responsibilities of the state and of individuals when it comes to public health.

Measles virus is spread by people coughing and spluttering on each other. The vaccine, which is highly effective, has been given with mumps and rubella vaccines since the 1970s as part of the MMR injection. The global incidence of measles fell markedly once the vaccine became widely available. But measles control was set back considerably by the work of Andrew Wakefield, which attempted to link the MMR vaccine to autism.

There is no such link, and Wakefield was later struck off by the General Medical Council for his fraudulent work. But damage was done and has proved hard to reverse.

In 2017, the global number of measles cases spiked alarmingly because of gaps in vaccination coverage in some areas, and there were more than 80,000 cases in Europe in 2018.

Anti-vaxxer threat

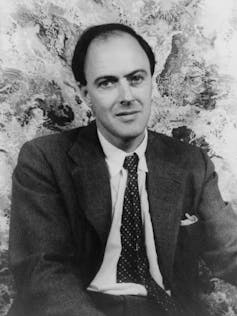

The World Health Organisation has declared the anti-vaccine movement one of the top ten global health threats for 2019, and the UK government is considering new legislation forcing social media companies to remove content with false information about vaccines. The recent move by the US authorities barring unvaccinated children from public spaces is a different legal approach. They admit it will be hard to police, but say the new law is an important sign that they are taking the outbreak seriously.Most children suffering from measles simply feel miserable, with fever, swollen glands, running eyes and nose and an itchy rash. The unlucky ones develop breathing difficulty or brain swelling (encephalitis), and one to two per thousand will die from the disease. This was the fate of Roald Dahl’s seven-year-old daughter, Olivia, who died of measles encephalitis in the 1960s before a vaccine existed.

When measles vaccine became available, Dahl was horrified that some parents did not inoculate their children, campaigning in the 1980s and appealing to them directly through an open letter. He recognised parents were worried about the very rare risk of side effects from the jab (about one in a million), but explained that children were more likely to choke to death on a bar of chocolate than from the measles vaccine.

Dahl railed against the British authorities for not doing more to get children vaccinated and delighted in the American approach at the time: vaccination was not obligatory, but by law you had to send your child to school and they would not be allowed in unless they had been vaccinated. Indeed, one of the other new measures introduced by the New York authorities this week is to once again ban unvaccinated children from schools.

Precedents

With measles rising across America and Europe, should governments go further and make vaccination compulsory? Most would argue that this is a terrible infringement of human rights, but there are precedents. For example, proof of vaccination against yellow fever virus is required for many travellers arriving from countries in Africa and Latin America because of fears of the spread of this terrifying disease. No-one seems to object to that.Also, on the rare occasions, when parents refuse life-saving medicine for a sick child, perhaps for religious reasons, then the courts overrule these objections through child protection laws. But what about a law mandating that vaccines should be given to protect a child?

Vaccines are seen differently because the child is not actually ill and there are occasional serious side effects. Interestingly, in America, states have the authority to require children to be vaccinated, but they tend not to enforce these laws where there are religious or “philosophical” objections.

There are curious parallels with the introduction of compulsory seat belts in cars in much of the world. In rare circumstances, a seat belt might actually cause harm by rupturing the spleen or damaging the spine. But the benefits massively outweigh the risks and there are not many campaigners who refuse to buckle up.

I have some sympathy for those anxious about vaccinations. They are bombarded daily by contradictory arguments. Unfortunately, some evidence suggests that the more the authorities try to convince people of the benefits of vaccination, the more suspicious they may become.

I remember taking one of my daughters for the MMR injection aged 12 months. As I held her tight, and the needle approached, I couldn’t help but run through the numbers in my head again, needing to convince myself that I was doing the right thing. And there is something unnatural about inflicting pain on your child through the means of a sharp jab, even if you know it is for their benefit. But if there were any lingering doubts, I just had to think of the many patients with vaccine-preventable diseases who I have looked after as part of my overseas research programme.

Working in Vietnam in the 1990s, I cared not only for measles patients but also for children with diphtheria, tetanus and polio – diseases largely confined to the history books in Western medicine. I remember showing around the hospital an English couple newly arrived in Saigon with their young family. “We don’t believe in vaccination for our kids,” they told me. “We believe in a holistic approach. It is important to let them develop their own natural immunity.” By the end of the morning, terrified by what they had seen, they had booked their children into the local clinic for their innoculations.

In Asia, where we have been rolling out programmes to vaccinate against the mosquito-borne Japanese encephalitis virus, a lethal cause of brain swelling, families queue patiently for hours in the tropical sun to get their children inoculated. For them the attitudes of the Western anti-vaccinators are perplexing. It is only in the West, where we rarely see these diseases, that parents have the luxury of whimsical pontification on the extremely small risks of vaccination; faced with the horrors of the diseases they prevent, most people would soon change their minds.

Tom Solomon, Director of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Protection Research Unit in Emerging and Zoonotic Infections, and Professor of Neurology, Institute of Infection and Global Health, University of Liverpool

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The Institute of Infection and Global Health. Powered by Blogger.